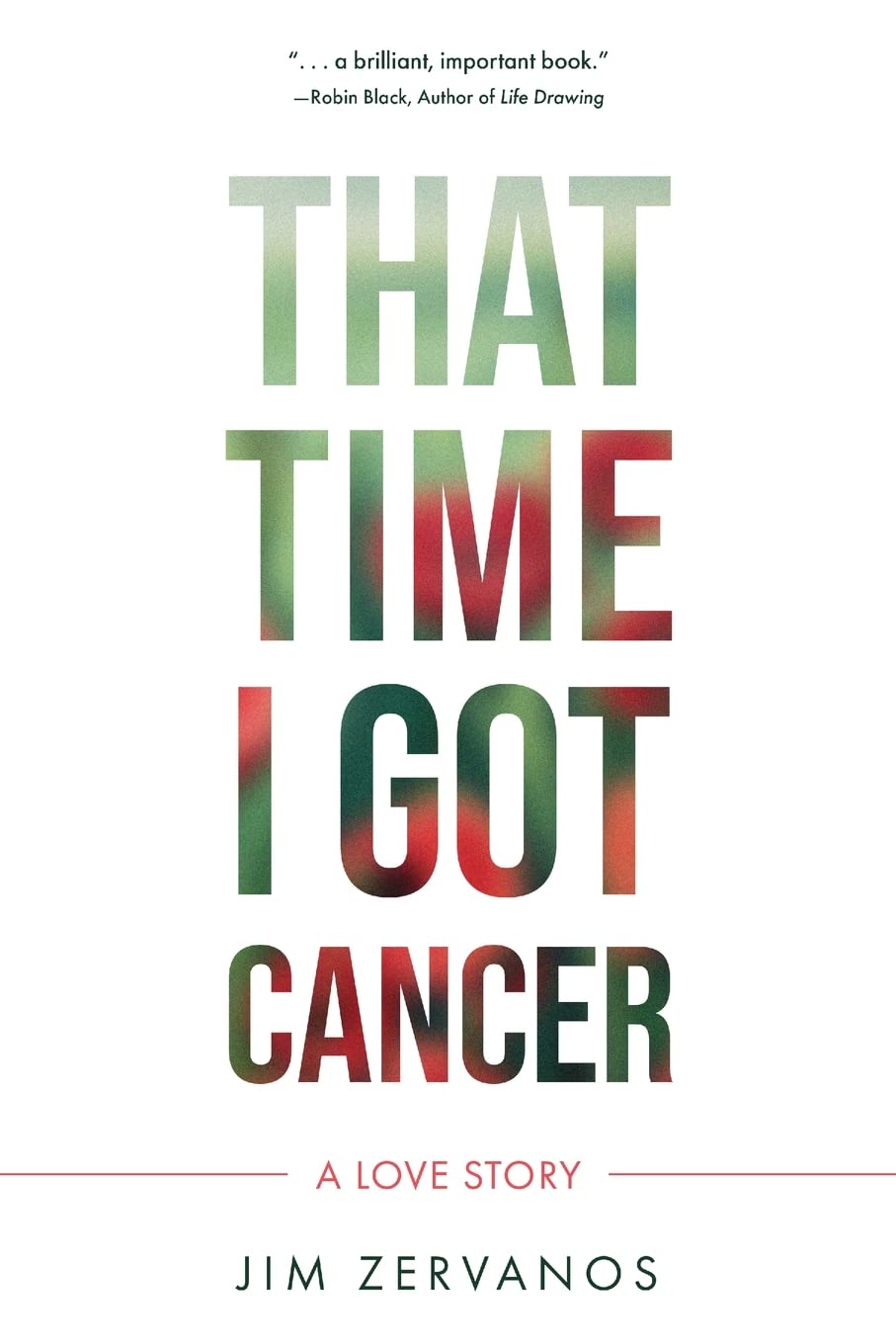

One minute Jim Zervanos was carrying his one-year-old boy to a baseball game; the next, he was in the ER, where for days he lay in limbo, being strangled from the inside. Teams of the best doctors were stumped by his worsening condition, before telling him there was nothing they could do.

That Time I Got Cancer: A Love Story is about experiencing joy even in desperate times. It’s about the relationships that anchor us, even as they must be entirely redefined. At forty-one, married, with a young son, Jim said goodbye to his family. When a brilliant new surgeon performed a radical operation, Jim was diagnosed with lymphoma, which led to chemotherapy and an uncertain road to recovery. Five years would pass before Jim began to understand what he had endured. Through mortality and back to life, this is the inspiring journey of a man awakened to the full experience of being alive and being present for it all.

Jim Zervanos is the author of the novel LOVE Park. His award-winning short stories and essays have been published in numerous literary journals, magazines, and anthologies. He completed the Narrative Medicine Workshop at Columbia University and is a graduate of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College and Bucknell University, where he won the William Bucknell Prize for English and was an Academic All-American baseball player. He teaches at a high school in the suburbs of Philadelphia, where he lives with his wife and two sons and has risen in the baseball pantheon as coach of two Little League teams.

1—Your new book, That Time I Got Cancer: A Love Story, came out this November. What inspired you to write it?

I didn’t write a word until I felt healthy and fully recovered—a year after the illness struck and six months after I’d finished chemotherapy. At first, I was motivated by practical concerns, to document the clinical story for my own safekeeping. But it wasn’t long before the whole saga came rushing out of me. I wrote in Philadelphia cafes for hours at a time and at a pace my fingers could hardly keep up with, sometimes with tears streaming down my cheeks. When I shared those earliest pages with my most cherished writer friends, they told me, you’re writing a book, keep it going. Only then did I learn that there was a whole distinct genre called the illness memoir, or the cancer memoir. Of course, I wanted my book to offer hope to patients and their friends and families who care for them, and I hoped to offer physicians and medical professionals a patient’s fresh perspective on matters of life and death. But I also wanted my memoir to appeal not just to a niche audience. I wanted my book to read like a novel, with universal appeal and a sense of urgency—a book that readers would pick up and not put down, and then rush to tell others to read it immediately.

2—All writers approach their stories differently. What was your process with this book?

Once I finished the first, much longer draft, I shared it with my family. There were parts that were hard for them to read—especially for my father, who, as a doctor, had felt helpless in those weeks when a diagnosis seemed elusive and when it seemed my life might be taken by an illness that would never be understood. Difficult as it was to revisit painful experiences, nobody asked me to cut a word. The conversations we had, sparked by those readings, were cathartic and satisfying for all of us, and led us to deeper understandings of our unique experiences. In my earliest draft, it was important for me to recall and express everything that seemed relevant to the story I was trying to tell, but eventually it became more important to cut what was unnecessary. To accomplish this, I had to figure out, or decide, what my book was about—beyond the clinical drama. As I revised, I focused on and dramatized the relationships that sustained me—thus the book’s subtitle: A Love Story. I cut numerous chapters; axed a whole storyline. When I discovered single scenes that could do the work of three, I cut the other two; and, inevitably, the scene that remained was better than all three together. I applied this same approach to every aspect of the writing.

3—How did you come up with the title of your book?

Early on, I emailed my writer friend to ask if she’d had a chance yet to read the first few pages I’d sent her about “that time I got cancer.” She replied, “I think you just found the title of your book.” But when I was completing the first draft, I came across the Nikos Kazantzakis quote that became the book’s epigraph, “We come from a dark abyss, we end in a dark abyss, and we call the luminous interval life.” I was convinced I had my title, “The Luminous Interval.” When I began sending out the book to agents and editors, one said the title was beautiful but obscure—which was also his criticism of the book; he insisted the book was too long and about too many things. So, I kept revising. I was five years in remission when I finished the final version, at which point the title “That Time I Got Cancer” had taken on new meaning, emphasizing that this was now a story set in the past—a revelation I included in the epilogue. I liked the idea that cancer patients, or people who have gone through trauma, could be drawn to the title, not only identifying with the awareness of their own mortality, but also recognizing hope in it—in the prospect of getting to the other side of their painful experience and one day having a story of their own to tell. I added the sub-title, “A Love Story,” to point the way toward the heart of the book, beyond the clinical story, where relationships are challenged and deepened, or even ruptured and repaired; the company of friends and family is comforting and healing; and doctors become confidants, partners in a great undertaking.

4—Who are some of your favorite writers or creators?

In college I was bowled over by fellow Pennsylvanian John Updike, by his lush style, familiar suburban settings, and stories of complicated young men I could identify with. My next obsession was Philip Roth, fellow Bucknell alumnus, whose intricately crafted narratives, both fiction and nonfiction, opened my mind to the amazing possibilities of what a book could do and how it could do it. My favorite poet is Walt Whitman. Favorite painters: Vincent Van Gogh, Jackson Pollack, Julian Schnabel. My favorite overall creator is Bruce Springsteen, who was my favorite even before he wrote his autobiography, a great book that now sits on the top shelf between Updike’s and Roth’s. These writers and artists are always evolving, pouring their whole selves into their work, marrying raw expression with mastery of craft.

5—How long have you been writing or when did you start?

I wrote my first short stories in a creative writing workshop as an undergraduate at Bucknell University. My early attempts were shameless imitations of John Updike’s short stories, which set me on the right path. Still, after college I completed three semesters at Temple Law School, before I realized that, if I really wanted to be a lawyer, I should be reading law books instead of novels, writing legal briefs instead of short stories, and getting an internship at a law firm instead of at the city magazine. That’s when I accepted the daunting fact that I wanted to be a writer. Luckily, I got a great job teaching high school English, and for twenty-eight years I’ve been a full-time teacher and writer.

6—What part of That Time I Got Cancer: A Love Story was the most fun to write?

I laughed out loud while writing two chapters that highlight how physically incapacitated I felt in the grips of chemo while trying to maintain a sense of humor. At a certain point, there was a kind of cracking open that occurred, a return to a sense of freedom that can only come with the belief that you just might be around for a while, after all. I found myself lampooning my own enfeebled condition—still incapacitated but suddenly fired up at the prospect of returning to normal life. In the chapter “Testosterone,” my friends are bantering in a group email, reveling in their vigorous lifestyles, each outdoing the other, coming off as parodies of masculinity; I stay silent for hours, absorbing all this, before rolling in with my own self-parody, recounting my chemotherapy regimen and subsequent bouts of nausea, with the passion of a sports announcer doing gametime play-by-play. In the chapter “Things We’re Looking Forward To,” I’m reading Esquire magazine’s four-page spread announcing every pop-culture event coming our way in 2012; at first, I’m skeptical that anyone’s life will be improved by the iPhone5 or Arnold Schwarzenegger’s memoirs. But by the time I get to the end, the list has me ecstatic to be alive, and now I can’t wait to see the new road-trip movie featuring Barbara Streisand as Seth Rogen’s overbearing mother—or at least to be on the planet when the movie hits theaters.